HOME  FORUMS FORUMS  NEWS NEWS  FAQ FAQ  SEARCH SEARCH |

A MICHAEL STONES ARTICLE

|

|

|

Editorial  Introduction to OPF Introduction to OPF Articles  Ricoh’s GR Digital II Review Ricoh’s GR Digital II Review by John Nevill by John Nevill   Nicolas Claris featured Nicolas Claris featured Sinar Photographer for 2008 Sinar Photographer for 2008  by Asher Kelman by Asher Kelman The Hard Side of Beauty The Hard Side of Beauty by Asher Kelman by Asher Kelman Canon EOS 1D Mark III Report Canon EOS 1D Mark III Report by Arthur Morris by Arthur Morris Seeing Like a Master Seeing Like a Master by Alain Briot by Alain Briot Photography As Art Series Photography As Art Series by Asher Kelman by Asher Kelman The other migrant mother The other migrant mother by Michael Stone by Michael Stone Fast Yachts at Sea, The Journey Fast Yachts at Sea, The Journey of a Captain & his Wife of a Captain & his Wife by Asher Kelman by Asher Kelman Rainer Viertböck’s Travel Rainer Viertböck’s Travel  Photography: Exposing for the Photography: Exposing for the  soul! by Asher Kelman soul! by Asher Kelman Tips for getting a human figure in Tips for getting a human figure in a location shot by Edmund Ronald a location shot by Edmund Ronald Stephen Eastwood an interview Stephen Eastwood an interview by Edmund Ronald by Edmund RonaldThe Team  Membership  About About Read TOS & Register Read TOS & RegisterSubmission  Articles Articles To offer services To offer services Donations Donations Adverts Adverts Sponsorships Sponsorships Contact Contact Meta.editorials In the forums Photography Exhibitions |

Early in 1936, photographer Dorothea Lange was driving home from a month’s assignment when she passed a sign for a peapicker camp near Nipomo in California. On impulse, she made a hurried detour to the camp, where she took a series of photos. That series includes Lange’s masterpiece: a portrait of a mother and her family, known thereafter as the Migrant Mother. Lange’s boss at the time, Roy Emerson Stryker, who headed up the New Deal’s photography project, described the Migrant Mother as the ultimate photo of the Depression Era, the picture of its time, and one that Lange and her cohort never surpassed. The acclaim still endures, as Stryker foresaw, eclipsing that of other great Depression era photos.

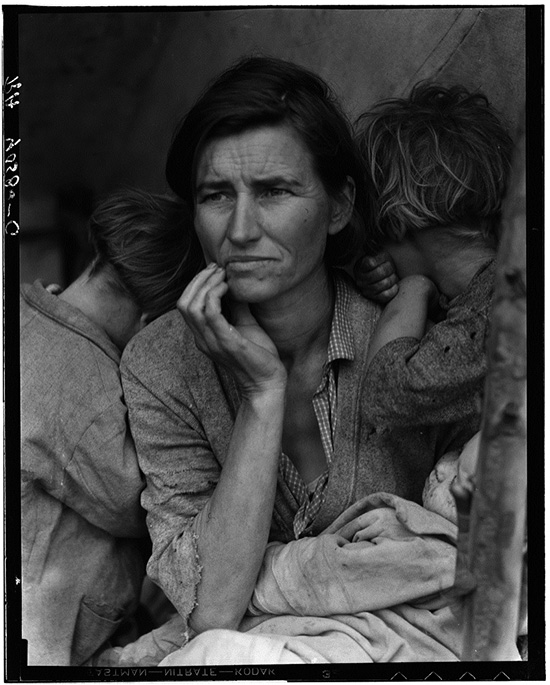

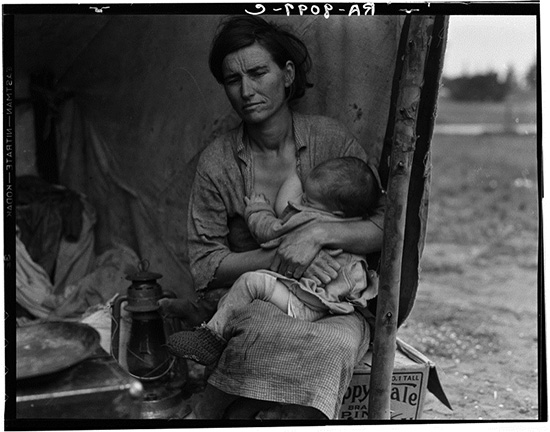

Lange’s titles her pictures locate them only with respect to demographics and geography (“Migrant agricultural worker’s family”, “Destitute peapickers in California; a 32 year old mother of seven children.”). She added a background to these terse descriptions in the February 1960 issue of Popular Photography. “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five [actually six] exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires of the car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me.” That help came quickly. Lange sent the photos to her employer, the Resettlement Administration in Washington, prompting a quick response by federal bureaucrats who rushed food supplies to peapicker camp. She also gave them to the San Francisco News, which featured two wide-angle shots in a March 10, 1936, article on the hardship endured by harvest workers. On the following day, it placed the iconic Migrant Mother picture above an editorial on the New Deal agenda. The ensuring uproar was a catalyst that inspired John Steinbeck to write his most influential novel, the Grapes of Wrath. All this hullabaloo came a little too late to help the family depicted in the photographs, which had already moved on from Nipomo. Forty years were to pass before the public even knew the mother’s name. A few years before her death in 1983, Florence Owen Thompson revealed her identity in a letter to a local newspaper, the Modesto Bee, stating her dismay about the iconic photograph. She felt exploited by it, never received a penny, and seemed hurt that the photographer never asked her name. Author and photographer Bill Ganzel did ask her name, resulting in his book Dust Bowl Descent that that the University of Nebraska Press published the year after she died. Another twenty years went by before Florence’s children gave journalist Geoffrey Dunn their version of the photo shoot in Nipomo for a 2002 issue of New Times Magazine. According to her children, Florence was not a new migrant to California, but a returning former resident. The family was on route to Watsonville hoping to find work in the nearby lettuce fields. Their Hudson car broke down by Nipomo, forcing them to stop and fix it at the peapicker camp. The photo session occurred while two older boys took the radiator into the town for mending. One of them, Troy, scoffed to Geoffrey Dunn that his mother never sold car tires to buy food: “There’s no way we sold our tires, because we didn’t have any to sell. The only ones we had,” he said “were on the Hudson and we drove off in them…. Mama told us there had been this lady who had been taking pictures, but that’s all she told us, you know. It wasn’t a big deal to her at the time.” They left that same day for Watsonville. “We were already long gone from Nipomo by the time any food was sent there,” said Troy. “That photo may well have saved some peoples’ lives, but I can tell you for certain, it didn’t save ours.” The five photos now archived in the Library of Congress are the creations of an artist while at the top of her talent. Dorothea Lange took them on 4*5” film with a Graflex camera. They show the mother, a baby, and up to three older children. The mother sits with a common posture throughout. She leans forward and to her right, toward the photographer but sideways into the tent, with her lower legs pulled slightly back. Her children’s postures are slumped, as if to convey defeat and resignation. Their faces (where visible) show no expression. The iconic image is a close-up. Two of Florence’s children are behind her and back-on, leaving little doubt about who is the central figure. She looks away from the camera, her face thoughtful, worried, her body inclined toward the flimsy dwelling, a baby on her lap. Her right hand, placed prominently against the face, pulling down the corner of a lip, shows a delicacy of manner that contrasts with the dirt under its nails. The mission given to Dorothea Lange by her boss Roy Emerson Stryker was to take pictures that would support the New Deal agenda of the Resettlement Administration’s (later known as the Farm Security Administration’s) documentary project. This agenda aimed to improve conditions for poor farmers and sharecroppers brought to poverty by the economic Depression. Stryker believed in scripting his photographers to capture in pictures the human side of pressing social and economic concerns of the day. With one exception, the Migrant Mother series seems to accord with this mandate. The clothing, faces, and postures depict the mother and children as ragged, broke, uneasy, resigned. Nobody departs from this profile. Nobody smiles. Only one photograph, #4 in the Library of Congress archive, depicts Florence Owen Thompson in a manner that looks unplanned rather than arranged. The older children are absent from Photograph #4, which is of Florence feeding her baby. She has a straighter posture than in the other photos, with her head bowed slightly downward and toward the tent. Her gaze seems inward, a private moment, as she glances down from the camera. Her expression shows no sorrow as the baby she cradles nuzzles her breast. The background shows the tent’s interior to her right, and to her left an out-of-focus landscape except for a box protruding beyond the tent’s outer pole. A flaw in the composition is that Lange angled the camera too low, cropping the top few wisps of Florence’s hair out of the frame.

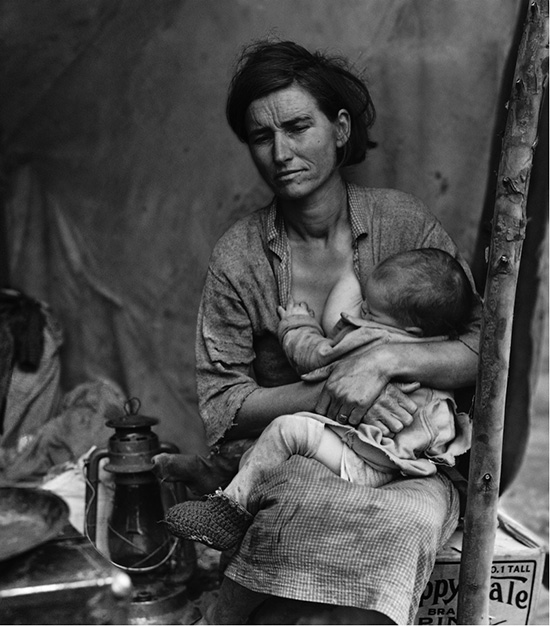

There are many reasons why Photograph #4 failed to become famous. Most compelling is that the Migrant Mother overwhelmed others in the series because of the power of its depiction of Florence’s plight. Also, newspapers of the time were unlikely to print a picture of a woman breast-feeding; the out-of-focus landscape adds nothing to the meaning; the overly cropped top of the photo was near to unfixable at the time. Unlike others in the series, Photography #4 seems like a snapshot Dorothea Lange took on impulse: a decisive moment she glimpsed and tried to catch but was unable to capture properly. This interpretation makes sense because none of the other photographs shows such errors in composition. Photograph #4 also conveys a different message from the rest of the series. Lange herself and those who published her pictures could hardly be unaware that Photograph #4 is less about Florence’s plight than her fitness to nurture despite that plight. A message that life goes on despite penury was not at the top of an agenda that Stryker’s agency sought to publicize. The humanistic documentary genre that Stryker’s photographers began has not been without reappraisal during the past seventy years. With the Migrant Mother, Dorothea Lange created an image that became iconic not only of the Depression years but of the genre itself. That photograph furthered the mandate that led to its creation beyond the dreams of any photographer of the time. But because that mandate was to show the human side of the Depression, should not the truths portrayed in the picture include those about Florence herself? The answer, according to Geoffrey Dunn, quoting from statements by her daughter (Norma) and son (Troy), is maybe not. Norma, the baby in the pictures, said of her mother that she “… was a woman who loved to enjoy life, who loved her children. She loved music and she loved to dance. When I look at that photo of mother [the Migrant Mother], it saddens me. That’s not how I like to remember her.” Troy recalled about his childhood years, “They were tough, tough times, but they were the best times we ever had.” Norma agreed: “We also had our fun.” We also had our fun: that is what is so notably missing from every face in Lange’s Nipomo series - a single smile that signals fun. Although Florence is not smiling in Photography #4, when unmindful of the camera she seemed content. What Dorothea Lange probably saw in that unguarded instant was a truth that transcended the situation. There was a woman engrossed in doing what she must and accommodated to her role in life. The photograph captures those facts about her. With its flaws repaired, it might provide a near-iconic image of motherhood but without the trappings of conventional sentimentality. Because the Library of Congress makes accessible 50+ megabyte digital files of scans of film negatives from the iconic image and Photograph #4, with no known restrictions on their use, insertion of upper parts of the former can help repair the latter. With Florence’s position similar in the photos, there should be little distortion resulting from this insertion. Consequently, I proceeded to repair Photograph #4 as follows. First, I stretched the canvas for Photograph #4 upward to make space for the top wisps of hair cropped from the film negative. Positioning, sizing, and matching of the luminance between the pasted insert and image were tricky but accomplished mainly with match color adjustment and the cloning tool in Photoshop CS2. I used the same tools to extend the tent pole upwards to match the new height of the image. With the new image not looking too ragged, the next step was to crop the blurred landscape from its right side and to darken the little that remained. The second stage of repair was to clean the image. The main task with the canvas was to ensure that the merger between the image and insert look seamless. So on a masked duplicate layer, I used shape blur, added Gaussian noise, then applied the texture filter to restore a canvas look. This process also got rid of dust and scratches present on the film negative. On the rest of the image, getting rid of dust and scratches (Oh, what a lot there were!) was tedious but routine with the cloning tool and healing brush. The result was a picture that was free from obvious flaws but in need of enrichment. Enrichment requires a Photoshopper to interpret the image. Interpretation in photography depends on what draws the eye. Good photos draw the eye to what is most important. Most important in this picture is the cradled baby nuzzling the breast. I used the diffuse glow filter to brighten the baby, the mother’s hands cradling it, and her breast, thereby drawing the eye to those parts of the image. Next most important is the mother’s face. I added a new layer and painted it white (but with low opacity and flow) near her right eye to reduce facial flatness and add verve. For the final corrections, I used curves to enhance midtone contrast and a Photolift plug-in to bring out detail in the darker areas and sharpen the image.

The newly repaired image conveys a message and a philosophy about photography that is distinct among the Nipomo series. If it is true that photography creates rather than mirrors a persona, then Dorothea Lange made Florence Owen Thompson the Migrant Mother based on a fixed agenda. Photograph #4 may be a truer likeness of Florence as she was then and in her future: a woman facing up to hardship, doing it by herself for her family, immersed in the moment. Florence showed that presence for a decisive moment that the hurried Resettlement Administration’s photographer was able to capture only imperfectly. Her gravestone, in Empire California, carries the inscription “Migrant Mother – A Legend of the Strength of American Motherhood.” The iconic photograph made the legend but the repaired version of Photograph #4 strikingly depicts a truth about motherhood as old as humanity. Michael Stones is an academic and active photographer, He's a Professor in the Department of Psychology, Lakehead University, Canada |

HOME  FORUMS FORUMS  NEWS NEWS  FAQ FAQ  SEARCH SEARCH |